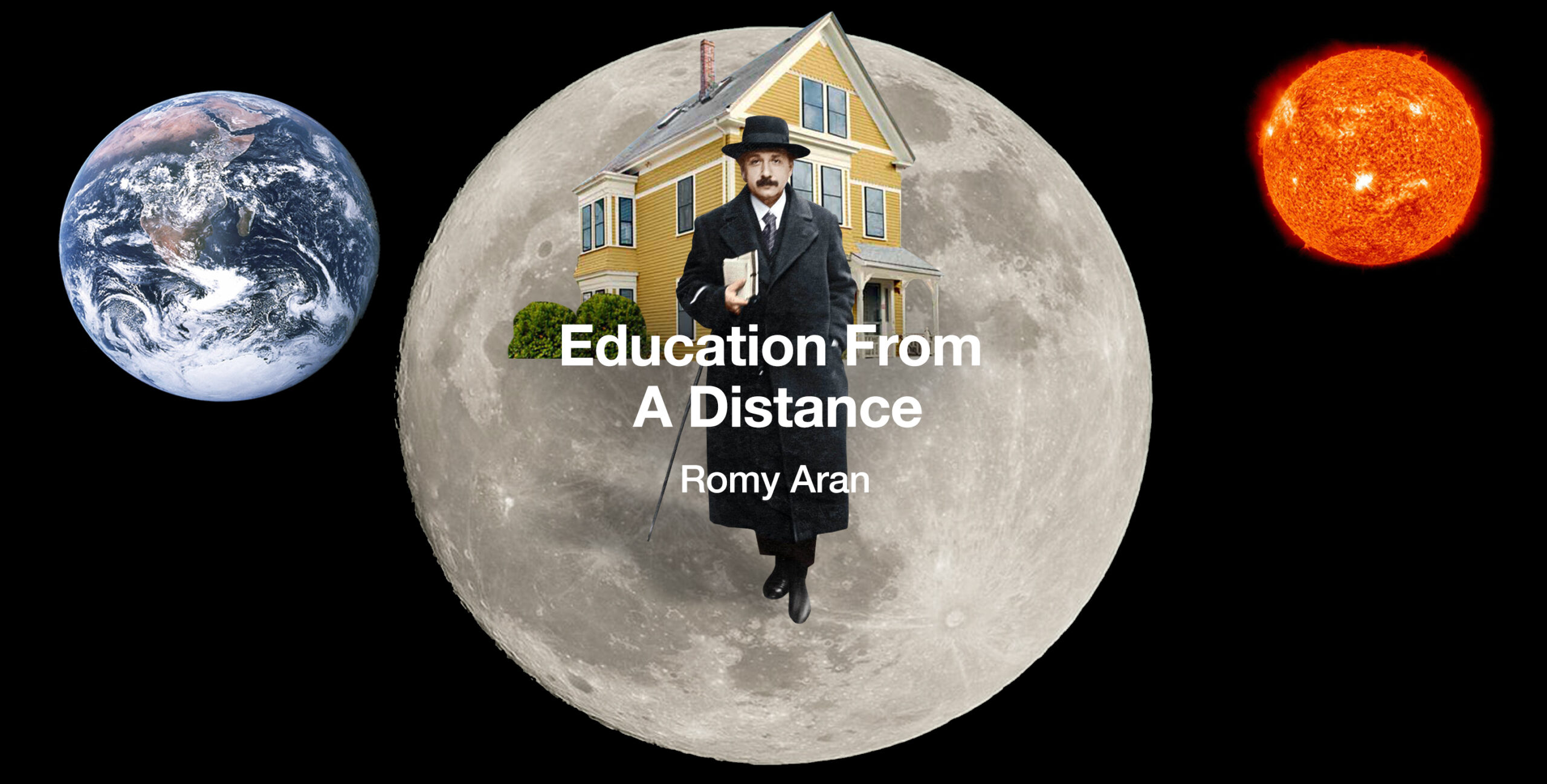

When the day reaches critical levels of heat, the atmosphere near ground level seems to undergo transitions that feel counterintuitive to our usual notions of how familiar matter, such as water, behaves when heated and cooled. That is one thing I gradually came to understand as I walked the three miles to the Highlands in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The day was wedged firmly in the crest of a wave of heat that crashed into the Northeast in late June. When I departed my room, I could still navigate. My legs could still swing easily and, in the midst of familiar territory, my progress felt real. As the distance shortened, the air began to liquify, even though the transition from gas to liquid is usually characteristic of cooling. By the time I arrived at my destination, of which I now simultaneously cared a great deal and couldn’t care less about, the heat had baked itself into the solid state, or like the gradually sinking surface of a non-Newtonian fluid. This bizarre heat landscape, with invisible icebergs of flame floating along the mild winds, found me in new geographies. I had left my room to travel to a distant location and get fingerprinted for an internship, but also to hopefully learn something about Cambridge on my walk. This town is a capital of education, and has been for centuries. The town itself, however, is as dynamic in living conditions and environments as the states of matter through which I was walking. What began as preparatory climbs through the cobbled streets of Harvard Square and the River Houses near Charles River, with buildings plucked from 17th century colonial America including the outrageous Winthrop House, which seems second only to Versailles in grandeur, eventually transitioned into the high-rise, block-towers studded with air conditioning units that rose like mesas in a vast desert. Coming from a city, trees and fields felt not like a return to “the land” but rather a convenient solution to dealing with more space than one knows what to do with. With very few people nearby, these fields looked more like abandoned factories than a field in nature. I came across, around the same time, a vast concrete cylinder. Concrete was lathered in layers up the side. Sprouting at the top was a large, healthy, but confusing tree. Why was it up there? Perhaps it had unknowingly becomea St. Simeon of the arboreals, submitting itself to great proximity to the Sun and educating itself in new and, to others, wholly unknown ways. I also cannot avoid the comparison with the Tower of Babel, a monument to the birth of language, according to the Christian tradition, or with the spiraling Great Mosque of Samarra. This structure, upon circumnavigating it, appeared to be the entrance to a parking garage. I was now a bit more educated in the ways of my own civilization: access to great heights and previously inaccessible realms of space situated within the atmosphere is no longer an escape from the material world but an expression of our embrace of it. And even when we leave the atmosphere, in our current times at least, we are beginning to hunger evermore for the materiality we worked so hard to abandon. Clearly this paradox is somewhat inherent in the very nature of bringing humans to an environment not inclined to give them the best chance of survival: the supply of basic resources must be guaranteed and perfected by the ground control team so that the minds above the sky are clear and can engage with the blue disk hovering out the window. What will one think when he or she sees this world from above? With commercial space flights steadily becoming a reality, many minds will be charged with this image: the image of a small and fragile world. But smallness and fragility, as history tells us, does not mean the same thing to everybody. Not everybody will be a student of the world which they departed, like the astronaut William Anders, who spoke of traveling for days across the vast, black desert of space to explore the Moon, only to end up discovering the Earth. We cannot control what one learns in their moments ofeducation, or even that the time granted is spent learning anything at all. Very often, the moment cannot be processed when experienced, and only days, months, or years afterwards, a lesson or message maybe distilled, like poor film soaking in weak chemical solution. In this light, I don’t think we got the most out of the experiences of Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong in the hurried requests for immediate reflections and accounts of their lunar excursion once they returned. The photons, yes, had not long ago scattered off the moon dust and impinged on their retinas. But the lesson learned must sometimes be gained over a wide gulf of time or space. Don’t we know that painfully in almost anything we have done which we have subsequently regretted? Scientists too, and mathematicians, philosophers, economists,... almost all fields, must grapple with an underlying reality which lies beyond a barrier, whether intellectual, methodological, financial, or conceptual. But that is almost a truism. But I suspect that the notion of distance is a deep one when it comes to study and education. If a thinker wishes to explore human nature, should they, like Nietzsche, reside in the remote mountains, or live in the bustle of urban life like Kant? History is scattered with thinkers shuttling between these worlds of remoteness and saturation, as if projecting and retracting their internal microscope. The pandemic has left us fixed in space, but dragged us along the current of time, making us something of a Nietzsche-Kant hybrid. I just hope to be educated from the experience, to not be left like driftwood in the wake of a terrible storm. We are all now returning from the Moon, or climbing down the spiral ramp of Samarra, or returning from a long walk in the heat of the Sun. We must ask ourselves, now or tomorrow, next week, or some other time: “Have we been educated? What have we learned?”

Other Pages

Interview with Dr. Alexandre SkibaProject type

The Return Of The HistoryProject type

A Dead DreamerProject type

NothingProject type

ObsessionProject type

A Person & Their TribeProject type

Education From a DistanceProject type

Coffee, Twitter, and RevolutionProject type

When I Turned SeventeenProject type

A Winter of IsolationProject type

SpeechProject type

Desolation's PerseveranceProject type

CoraProject type

Hospital CookiesProject type

A Fragmentation of WordsProject type

The Stress of Remote LearningProject type

Sweet SixteenProject type

WordsProject type

A Christmas CarrollProject type

New York City 2020Project type

Qualified Immunity: Broken DownProject type

What Science Tells Us About Gender?Project type

Beyond The Bathroom StallsProject type

1 am thoughts on Trutharticle

Brooklyn, NY During COVID-19Photo Gallery

AboutAbout Page

Submission InformationProject type