In the last decade, the issue of gender identity has become a political hotspot; a question of bathrooms, feminism, and whether or not some persons' gender jeopardizes their human rights. With A-list celebrities like J.K. Rowling tweeting blatantly transphobic statements such as, “If sex [E.g: the sex of a child at birth] isn’t real, the lived reality of women globally is erased,” discovering what gender truly means has become an increasingly more difficult task.

However, the controversy surrounding gender identity has yet to keep people from attempting to define it. Currently, the World Health Organization, or WHO, defines gender as, “described interms of masculinity and femininity... a social construction that varies across different cultures and over time.”It’s a definition that implies that--contrary to Rowling’s assertion-- gender is a wide spectrum of ideas, emotions, and the lived experience of every individual. It is this definition that will be explored throughout the rest of this article, comparing it to both recent scientific discoveries and past definitions.

Transgender, a term used to describe people who are born one sex but identify as the opposite sex, has historically been defined through a psychological lens. According to Katherine J. Wu, in the article, “Between the (Gender) Lines: the Science of Transgender Identity,” some scientists, in the past, have gone as far as to describe being transgender as “apsychological disorder.” More recently, such definitions have since been widely discredited fortheir transphobic connotations. As scientists continue to research and learn about the aspects of gender identities, new scientific findings provide a different perspective on modern day gender roles, creating a path to a revolutionary way of viewing “gender,” and in the process rendering a new way for the next generation to find and define themselves.

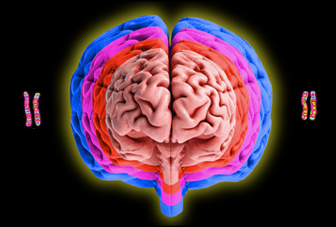

Traditionally, the term “sex” has been used to describe humans on the basis of reproductive organs, sorting people usually into two categories; “male” or “female.” It may be clear to any person, scientist or not, that this definition is limited in its ability to describe every individual human. In fact, it may not even be an entirely correct definition. Recent scientific findings indicate that sex is determined by a complicated mixture of chromosomes, hormones, and genes.In other words, what makes up a person's gender identity is not a clear path, but a long winding road that has many different features. The research paper “Brain Sex Differences Related to Gender Identity Development: Genes or Hormones?*” tries to map this road. This paper defines gender as an inner sense of being, and provides a scientific explanation for why some people feel as though they were born in the wrong body.

The paper highlights how the aspect of gender identity is unique to humans, and one’s genderidentity may be defined by more than just an X or Y chromosomes. Rather, an individual'sgender is a product of genes and sex hormones, as recent discoveries in biological sciencesfocusing in on neuroanatomy and sexual dimorphism tell us. A sexual diamorphic brain meansthat humans’ biological sex causes differences in both sexual reproductive organs and otherorgans, such as the brain. Sexual dimorphism also implies that sex and sexual tendecies maybe shaped by genes and hormones, in addition to chromosomes. In fact, studies focusing on the anatomical differences in cismen and ciswomen have discovered differences in function between total brain volume, cortical thickness, and the hippocampus, among other aspects. These differences bring upon a larger question of what makes up a gender and a person’s sex, and as research deepens, the answer becomes increasingly unclear. However, further research also provides evidence to show that when transgender individuals feel as though they are born in the wrong body, they may be, biologically, a female in a male’s body.

In Katherine J. Wu’s article, she cites the differences in the chemical makeup of a transgender woman’s brain compared to that of a cismale’s brain. Wu also notes previous studies that show that transgender females have a chemical makeup of the brain that aligns with ciswomen more than cismen. This is found when comparing a part of the brain--one known as the bed of the Stria terminalis (BSTc)--between biological males and females, both sexually dimorphic. In humans, this area of the brain is known to have estrogen receptors. Wu notes inher article that the makeup of the BSTc in cisfemales in strikingly similar to that of transgender females: in cismales, the BSTc is twice as large and much denser with more neurons than cisfemales. However, in transgender females, even with horomonal treatment taken into account, their BSTc seem to be smaller, and more spread out. On a biological level, the brainfunction of a transgender female, prior to any hormonal treatment, already better matches with the percieved gender identity of the individual, rather than their assigned sex at birth.

It should be noted that the science in this region is new and limited. But with more transgender voices being heard in the last decade, these findings will help pave the way for new and more inclusive perspective on the of viewing of “gender” as something completely separate from one’s assigned sex at birth. In fact, future generations may find that gender is more of a complex spectrum defined by a long list of influences that make up one person, rather than a simple “male” or “female.” Thus, tweets such as Rowlings are not only transphobic, they are scientifically incorrect, and fail to incorporate the complex reality of gender.

Works Cited:

Chung, Wilson C J, et al. “Sexual Differentiation of the Bed Nucleus of the Stria Terminalis in Humans May Extend into Adulthood.” The Journal of Neuroscience : the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, Society for Neuroscience, 1 Feb. 2002,www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6758506/.

Luders, Eileen, et al. “Regional Gray Matter Variation in Male-to-Female Transsexualism.”NeuroImage, Academic Press, 31 Mar. 2009,www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1053811909003176?via=ihub.

Ristori , Jiska, et al. “Brain Sex Differences Related to Gender Identity Development: Genesor Hormones?” International Journal of Molecular Sciences , 19 Mar. 2020, doi:10.3390.

Wu, Katherine J. “Between the (Gender) Lines: the Science of Transgender Identity.”Harvard, 25 Oct. 2016,sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2016/gender-lines-science-transgender-identity/.

*Written by: Jiska Ristori1,†,Carlotta Cocchetti1,†,Alessia Romani1, Francesca Mazzoli1, Linda Vignozzi1 Mario Maggi2 andAlessandra Daphne Fisher1,*

Other Pages

Interview with Dr. Alexandre SkibaProject type

The Return Of The HistoryProject type

A Dead DreamerProject type

NothingProject type

ObsessionProject type

A Person & Their TribeProject type

Education From a DistanceProject type

Coffee, Twitter, and RevolutionProject type

When I Turned SeventeenProject type

A Winter of IsolationProject type

SpeechProject type

Desolation's PerseveranceProject type

CoraProject type

Hospital CookiesProject type

A Fragmentation of WordsProject type

The Stress of Remote LearningProject type

Sweet SixteenProject type

WordsProject type

A Christmas CarrollProject type

New York City 2020Project type

Qualified Immunity: Broken DownProject type

What Science Tells Us About Gender?Project type

Beyond The Bathroom StallsProject type

1 am thoughts on Trutharticle

Brooklyn, NY During COVID-19Photo Gallery

AboutAbout Page

Submission InformationProject type