I’ve noticed that as I slowly make my way through the weaving canyons of human thought, relics from past floods of revolutionary insight, the traces of female scientists and mathematicians begin to make themselves known. While these days anyone can go on the internet and, with a little research, discover these names for themselves, the narratives which are taught in our elementary, middle, and even high school education systems neglect to make these figures known. STEM fields are so often presented as tightly bound collections of knowledge that forge a path without mystery, drained of its complexity, and left utterly inhuman. The human comes from the drama, the trials of courage that scientists faced to make their findings, the leaps of insight taken and those just barely missed. And of course, the human is found in the clash between society and science.

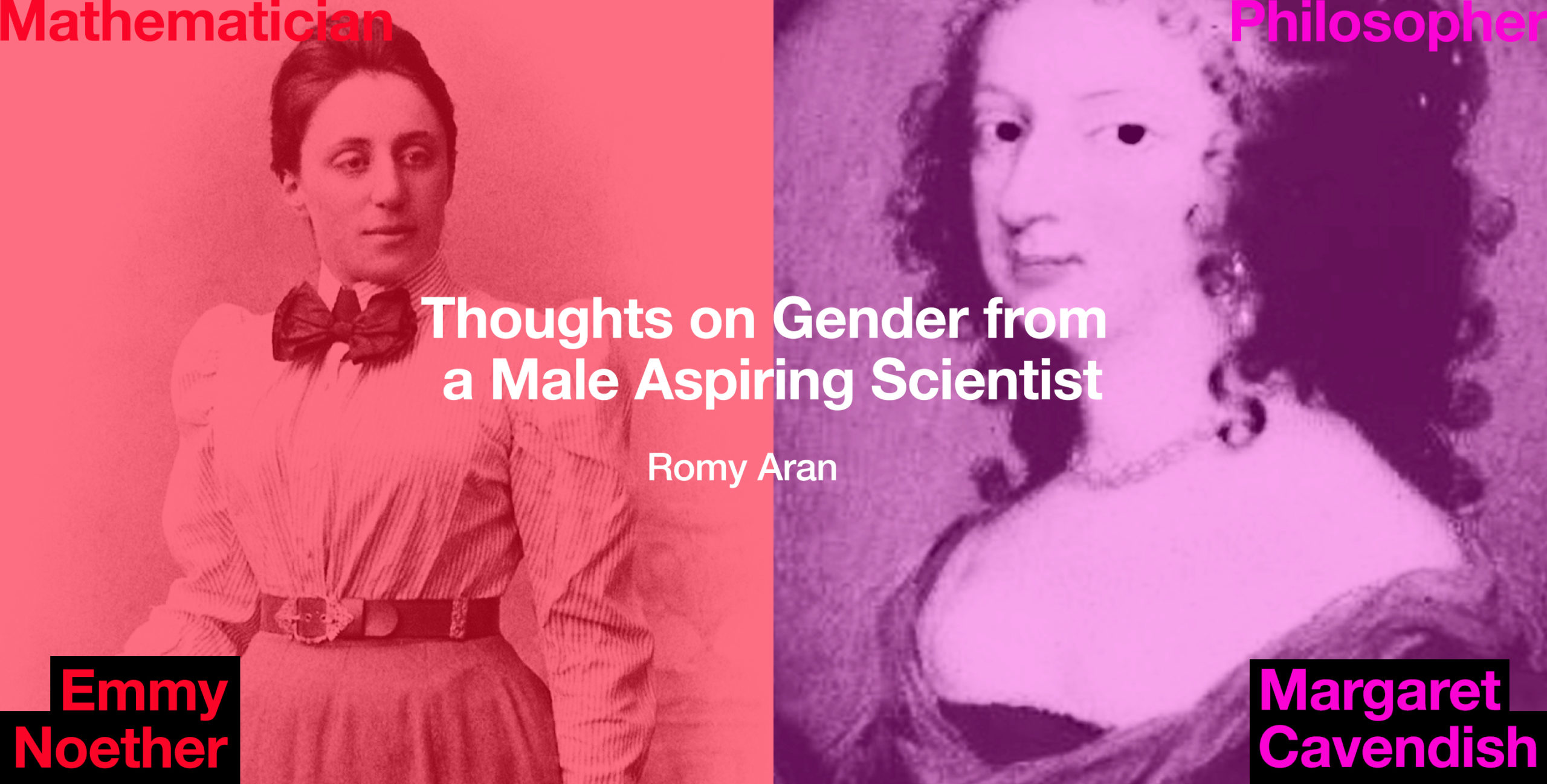

The revelation that the ways we think about the world in fact reflect human bias is not a new orparticularly original one. But it is worth noting that science has a long tradition of conflicting with existing governments and social institutions. This fact says more about the institutions we adopt, the influence which they exert on their local societies and the cultural, political, and ideological spheres which they seek to re-define. Perhaps the earliest, and most frequently cited, example of such a clash is the condemnation of Galileo’s Copernican leanings by the Catholic Churchin 1633, when he was put on trial by the Inquisition. More recent examples include the ridicule received by Darwin’s theory of evolution and the persecution of Jewish mathematicians and scientists in Europe under the Nazi regime. In each example, the institution challenged saw a particular form of opposition presented by the threatening scientific practice, whether a challenge of religious doctrine, notions of racial superiority, or speciesism. However, unlike each of these instances, the presence of women in academic circles presented an almost continuous challenge to the traditional institutions of the day, one that was so controversial that it continued to raise criticism from the era of Aristotelian physics to the era of relativity. A notable example of this is seen in the difficulty faced by Margaret Cavendish, the mid-17th century British natural philosopher, in gaining access to the newly founded Royal Society, despite her numerous and wide-ranging publications in the natural sciences and philosophy. While finally given permission to attend a meeting, she was called “conceited” and “ridiculous”[1] by contemporaries. Her ideas laid out the remarkable possibility that the particles which compose matter exist in a state of constant motion, a concept which is now known to be true[2]. Interestingly, she also broke boundaries in writing what is considered by many to be the first work of early science fiction[3]. Another notable example is Emmy Noether, the brilliant mathematician who, despite her revolutionary contributions to pure mathematics and physics, faced tremendous opposition by faculty members in the University of Göttingen, where she was invited by the renowned mathematicians David Hilbert and Felix Klein [4].

The resistance towards female mathematicians and scientists among their male colleagues reflects the hypocritical and overall deep fact that the insights made by human beings have for centuries not been disentangled from the minds which produced them. The mind which made the discovery, and the body which hosted the mind, had a decisive impact on whether that idea would flourish or be neglected, meaning that for the greater part of the existence of modern science, scientific investigations were treated (by the wider community of scholars) not as the crystalline fragments of universal insights which they professed but as the self-complementary reflections of like-minded, like-bodied individuals. The human drive to claim for a particular party or collective, at the expense of others, is just as powerful in the theoretically platonic ambition of scientists and mathematicians. If anything, the beauty of the universality of the deep insights produced by these fields, so clearly capable of being discovered by people from all backgrounds, should be a source of hope and inspiration for the eradication of the wider biases and condescension faced by people of all ages across the world. The lesson of how long and how deep exclusion of ideas on the basis of gender has lasted should pave the way for a broad re-assessment of how scientists are educated, particularly in the humanities, so that science will not degenerate into yet another arena for exclusionism and discrimination but be the gift of liberated exploration of the universe for all human beings. This is easier said than done and is particularly difficult because, for many institutions, the track of a STEM degree does not require complementary studies of ethics, philosophy, social science, and/or history. As our world heads towards a computing renaissance, understanding the capacity of scientists to either encourage the richness of human thought or to stifle it, and even to cause tremendous harm, must be assessed, since never before has the power of scientists been greater, and likewise their obligation to others in their community and to all of humanity has never been a higher priority.

Works Cited:

[1]Narain, Mona. “Notorious Celebrity: Margaret Cavendish and the Spectacle of Fame.”The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association, vol. 42, no. 2, 2009, pp. 69–95.JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25674377. Accessed 28 July 2020.

[2]Newcastle, Margaret Cavendish.Philosophical Letters, or, Modest Reflections upon Some Opinions in Natural Philosophy. 1664.

[3]Spender, Dale.Mothers of the Novel : 100 Good Women Writers before Jane Austen. Pandora, 1986.[4]Brewer, James W., et al.Emmy Noether : a Tribute to Her Life and Work. M. Dekker, 1981.

Other Pages

Interview with Dr. Alexandre SkibaProject type

The Return Of The HistoryProject type

A Dead DreamerProject type

NothingProject type

ObsessionProject type

A Person & Their TribeProject type

Education From a DistanceProject type

Coffee, Twitter, and RevolutionProject type

When I Turned SeventeenProject type

A Winter of IsolationProject type

SpeechProject type

Desolation's PerseveranceProject type

CoraProject type

Hospital CookiesProject type

A Fragmentation of WordsProject type

The Stress of Remote LearningProject type

Sweet SixteenProject type

WordsProject type

A Christmas CarrollProject type

New York City 2020Project type

Qualified Immunity: Broken DownProject type

What Science Tells Us About Gender?Project type

Beyond The Bathroom StallsProject type

1 am thoughts on Trutharticle

Brooklyn, NY During COVID-19Photo Gallery

AboutAbout Page

Submission InformationProject type